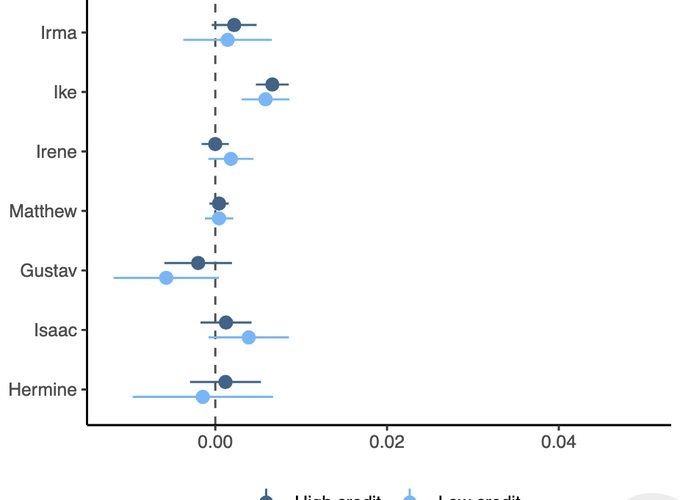

We use credit bureau microdata containing the quarterly locations of 20 million Americans to examine migration responses to 10 hurricanes between 2005 and 2017. We find that flooding from the largest hurricanes caused small increases in migration in the two years following the largest storms, while smaller hurricanes or exposure to high winds alone have limited effect on migration patterns. The results do not vary with individual credit scores, suggesting that credit constraints do not substantially affect migration. Despite short-term increases in migration following large storms, we find that Hurricane Katrina is the only storm that caused a meaningful long-run population decline in flooded areas. Our findings show that except for the most catastrophic hurricanes, post-disaster migration is unlikely to decrease population exposure in hurricane-prone areas.

Blonz et al. (2025)

Blonz et al. (2025)